I was a teenager once…

I get it.

Ugggggh…

Kids These Days.

This project needs to get done quickly…

we don’t have time to involve people along the way.

Teens think they know everything…

they’ll see I’m right when they get older.

But really, this chapter is for everyone, because how you show up in youth voice work is foundational, and this work of self-reflection is a continuous process.

Integrating youth voice into our research methods and processes has profoundly changed our work. It has challenged not only what we know, but how we think about expertise, what we think of as data, and how we think about rigorous evidence. It has also been delightful and fun!

Being willing to take youth expertise seriously – as seriously as you take your own expertise – can take a lot of intellectual humility. And being self-reflective in this way can be hard! So let’s start with talking about why youth voice is so valuable, and then move into how to do the personal reflection and preparation necessary to engage in this meaningful work.

Why youth voice is so important:

Transform your understanding.

Involving young people in your research can totally transform your understanding of a topic. As researchers or developers we often have expertise or theoretical understanding of a topic. But we rarely have the current, lived experience of what it feels like for young people who experience it in their own lives – and this is another essential kind of expertise. At the minimum, young people’s stories about how a topic impacts them give us rich qualitative data that paints a better, more nuanced picture of the issue. In other cases, young people might help you realize you had totally misunderstood something and need to go back to the drawing board.

Example from Character Lab

We were doing an evaluation of an SEL program in partnership with schools. Kids sometimes seemed disengaged during the lessons, and one of the assumptions school leaders and teachers had was that students found the content uninteresting. However, when we actually sat down and talked to students about the curriculum, they said the content was mostly fine. The issue was something else: they pointed out a gap between the values that the school was promoting through the curriculum and their actual lived experiences with the rules at their school. For example, one student said:

“They say they care about community, but lunch is too short. It’s only 20 minutes; there’s not enough time to socialize or just hang out with my friends that I don’t see [during the rest of the school day]. And we get demerits for how we hang out at lunch!”

School leadership hadn’t recognized this gap between the values that they were hoping to strengthen through the SEL program and students’ experiences of the school culture. But it was influencing the outcomes of the SEL program. Thus, instead of focusing on the content of the SEL curriculum, we redesigned our evaluation to focus more on school culture and its impact on the SEL outcomes the school was hoping to achieve.

Ask better questions.

Working with young people can help ensure we’re asking good questions. Involving young people in research helps ensure the reliability and validity of the research itself by continuing to check that the research is relevant to youth and their lived experiences (Cheney, 2011; Thomas & Kane, 2006; Green, et al., 2022).

Example from HopeLab

Codesigning the third wave of our national survey on youth social media use and well-being with teens and young adults transformed the survey’s focus in foundational ways. The young people who helped build the survey pointed out the numerous and nuanced positive experiences they have on social media that often go overlooked by adults – for example, how critical social media is to LGBTQ+ youth for finding an affirming community that they may lack in-person. Additionally, while many young people were deeply aware of platform design features that make it difficult to control their social media usage, they also pointed to adaptive ways they exercise agency over their online experiences, like taking strategic breaks from certain accounts. By involving young people in the design of the survey questions, Hopelab and our partner Common Sense Media were able to ask more meaningful questions that better captured the complexities of young people’s relationships to social media.

Avoid misinterpreting.

Involving young people directly in the research helps mitigate risks of misinterpretation (Coyne, S., Weinstein, E., Andan Sheppard,J. , et al., 2023). We can all think of times when we misunderstood what someone meant. In cross-cultural, cross-generational, or virtual settings, the likelihood of misunderstanding is even higher. Inviting youth to help you co-interpret data you’ve collected – explaining their views on emerging findings or insights – can help you to analyze and understand your data. It also lets you dig into nuances like sarcasm, mixed feelings, tension, cognitive dissonance, or humor that you might otherwise miss.

Example from Center for Digital Thriving

Youth voices can be especially essential when you want to understand why particular subgroups of youth appear to have meaningfully different experiences from their peers. One of our colleagues who studies social media and mental health collected survey findings that revealed gender identity moderated not only the strength but also the direction of multiple associations between social media practices and mental health. We collaborated with her team to integrate co-interpretation into their research process through advisory groups that included both cisgender and transgender/non-binary (TGNB) teens, facilitated by cisgender and TGNB adults. The research team then included voices from those youth advisors in their study’s discussion section; here is an excerpt from the published article:

“Taking intentional technology breaks was significantly associated with increases in depression and emotional problems for TGNB youths but not for cisgender youths, again suggesting the balance of risks and benefits of youths’ SMU differs by gender identity. For TGNB youths for whom social media is a key venue for social acceptance, breaks could cut this off and potentially be detrimental to health. As a TGNB advisory board adolescent explained, ‘I’m fine taking breaks because I already have a support group that is super nice to me. For others, when they delete it, [they delete] their safe place. That’s why they feel bad…they don’t have that community anymore.’”

Get new ideas.

Working with young people can give us new ideas for interventions and resources that are relevant to their lives. Sometimes we realize that there’s a topic we haven’t been addressing at all, but we should be. In this way, young people can help identify and correct our blind spots!

Example from Center for Digital Thriving

As our team has engaged with teens about their experiences with smartphones and social media, we’ve learned a lot about the kinds of experiences that can be stressful or anxiety-provoking, in big and in small ways. One example is being left “on Read”: when you can see that your message has been delivered, received, and opened/seen, but the other person hasn’t replied. Teens shared with us how this can spark a thinking spiral:

Why haven’t they replied? I shouldn’t have sent that message. They think I’m dumb. They hate me now. We also heard about thinking spirals that can be sparked by scrolling: Everyone I follow is so much happier than me. Goes out more. Has more friends. Has their s*** together. Is doing more. Is doing better.

In both cases, we recognized connections to common cognitive distortions, and we started to appreciate how evidence-based insights from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) could be relevant. We then worked with youth, educators, partner organizations, and clinical psychologists to co-create a glossary, lesson, and video about Thinking Traps (all of these Thinking Traps resources are available here).

Support young people.

Finally, involving youth in research benefits youth participants themselves! There is ample evidence that youth participatory action research methods can facilitate agency, including building trust and empowerment through working in solidarity with peers (Martin, Burbach, & Benitez, 2019). Even beyond YPAR, knowledge gained from being involved in the research process can also support young people in taking further action independently about topics of importance to them.

Example from Character Lab

Many students who participate in research find an interest that lasts into their college and adult years. Character Lab ran a youth voice program (“CLIP”) with high school students for over 5 years, and many alumni went on to college to pursue degrees in psychology, sociology, and other applied research fields. Of course, many of them were interested in these topics before they joined CLIP, but many also said that they had signed up for CLIP not knowing anything about research, and through the experience realized a new interest. In the words of one CLIP alum:

“I truly believe that the CLIP program and my experience as a CLIPster has helped me develop many competencies that are now essential for my success in college! Thank you!”

Doing the work to prepare:

Now that you’ve read a few of the reasons why partnering with youth is so valuable, let’s dive into how to prepare to do so in a meaningful way. Any time young people and adults are working together, there are power dynamics at play. Adults – especially “researchers” – have authority, money, knowledge, and prestige. If we are not intentional about how we show up to this work, we risk alienating, tokenizing, offending, or using young people.

This section is meant to give you some food for thought, but we also want to be up-front about the reality that you’ll need to continuously return to this personal work. Unlike a microwave burrito, it’s not a quick fix. As you get older, as youth cultures continue to change, as new technologies emerge, and as circumstances in the world evolve, your own positionality and how you show up with young people will also change – and therefore, it’s important to adopt a posture of continuous learning. Hopefully this section will give you some tools to do that! Here are some of the guiding principles we find helpful.

Don’t lead the witness(es).

If you’re doing youth voice work to feel better about a decision you’ve already made…. don’t. Have you identified areas of your project you are genuinely interested in improving and co-creating with youth? Or are you asking them for some quick stamps of approval on work you’ve already pretty much finalized? If it’s the latter, that’s not the type of youth voice we’re talking about.

There are some parts of the research process that lend themselves more easily to youth participation, like reviewing methodology and tools, data collection, and data interpretation stages. Few research projects include youth at all stages of research (Fløtten, K. J., et al., 2021). We believe that there are meaningful upsides to engaging youth at all different stages of the project lifecycle; it just depends on the value and impact you are ultimately trying to achieve.

A few questions to consider:

- What do you know the least about or have the least experience with? What areas of your work do you sense are most ripe for youth voice?

- What parts of your project are actually up for discussion? Are there non-negotiable phases?

- If youth were to give feedback at ‘x’ point in the project, could you realistically implement their insight?

To be clear, it’s totally ok to set parameters for where you’re inviting youth engagement – and where you’re not. You just need to be clear with yourself, and then with the youth you involve, about which parts of a project you’re asking for them to help with, which parts you’re not, and why. Ask your team before you begin: what would change about our direction if youth shared one perspective vs. another? What are we really willing to change our minds about? Invite youth to join you in the sections of the project where their influence will really matter; otherwise their participation can feel (and be) tokenistic.

Figure out what you really want to know.

Do you want young people to help you interpret data you’ve already collected? Do you have a question that you really don’t know how they’ll answer? Are you genuinely curious about and open to the direction young people’s perspectives will lead? Document what you already know and (if applicable) emerging findings from prior phases of your work so you can identify the gaps that youth voice research can help you fill.

Clarify who you want to learn from.

Young people aren’t a monolith. It’s helpful to think carefully about the young people whose voices, perspectives, and identities you want to hear from (more on this and on recruiting in chapter 4.) But even if you have selected a really specific demographic group, remember that your participants still can’t speak for their entire group – even if that group is super specific, like “15-year-old evangelical White girls from rural Iowa who play the bassoon.” Your youth partners are individuals as well as representatives of a group; holding those two things together is an important part of doing this research with validity.

Respect their expertise.

Most of you reading this playbook will have more advanced degrees, years of life lived, and career experience than the young people you engage in your projects. You probably do know more about psychoneuroendocrinology or product development or whatever, but that’s not why you’re inviting youth to your project. You’re inviting them because they are subject matter experts in a subject you’re not an expert in: being a teen today. That expertise is valuable! It should be respected and compensated, just like other external experts you’d invite to join a project. (More on this in chapter 3.)

Be aware of etiquette, vocab, and cultural norms.

We are not trying to make young people sound like they’re from another planet – that trope has certainly been done enough. But it is true that young people often have ways of communicating, slang, and norms that are different from the ones you may use. Don’t try to talk like a teen, but do be ready to talk authentically with teens! You don’t want to be trying too hard (nobody wants their adult facilitator to tell them their answer “slaps”) but you also don’t want to be googling “what does yeet mean” on the side. If in doubt, just ask.

It’s also really important to think about how the words you use can create an inclusive space (or not). For example, our teams all ask people to include their gender pronouns when they introduce themselves at the start of a meeting, in order to make space for transgender, non-binary, or non-gender-conforming folks to introduce themselves comfortably and hopefully avoid being misgendered. This is becoming more common, but if it’s a new practice to you, we link to more resources about this below.

Keep an open mind and be flexible.

No matter how much you prepare, the reality is that you may not know ahead of time what is most important. Youth will guide you in directions you might not predict or expect. Come with an openness to the unexpected, and (if possible) a timeline that allows you to iterate and change your initial plans based on youth feedback. (More on this in chapter 3, Budgets & Resources.)

Resources, activities, and digging deeper

Reflection & planning guide

This worksheet, which was adapted from resources by Ahna Suleiman, can be used for personal reflection or leading a group conversation with your team as you’re. young people for the first time in a new project.

A youth leader’s guide to building cultural competence

This is a long resource, but chapter 2 includes some useful personal reflection questions focused on your own identity and positionality and how this might impact how you interact with young people.

Pronoun guide

This is a good primer from GLSEN on using inclusive pronouns.

Creating culturally responsive programs

This resource from Virtual Lab School covers a bunch of topics related to culturally responsive teaching, including addressing implicit bias, incorporating anti-racist strategies, and designing equitable environments.

Youth and adult power-sharing

These resources are part of UC Berkeley’s Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) Hub. In particular, these address adultism and some of the embedded power dynamics you should think about before beginning a project in partnership with youth.

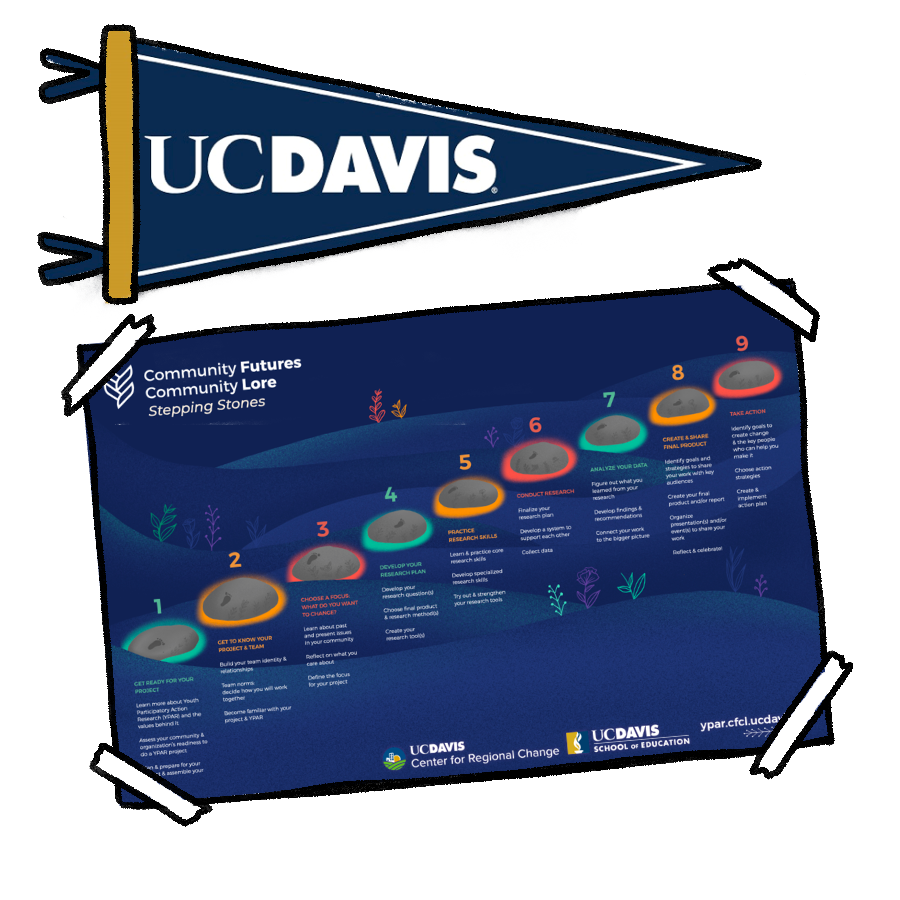

Stepping stones

These resources from UC Davis are also YPAR-focused, but also have a lot of relevance for other research approaches with young people. In particular, stepping stone 1 is super relevant to the content of this chapter.

Youth and adult power-sharing

These case studies, from CDT and Hopelab, provide step-by-step examples of how the two research teams enhanced their practice by collaborating with young people at strategic points in the research process. They serve as a useful complement to the YPAR guides, offering models of how to engage young people in research in lighter touch ways.

What to Read Next

OK, you hopefully agree that research about youth shouldn’t happen without youth, and you’re on board to go find some youth partners! Before you hang posters all over town, though, let’s stop for a second to think through ethical and regulatory considerations – these need to be on your radar before you invite a bunch of young people to come hang out at your team’s office. Turn to chapter 2 for more on Ethics, Laws, and Keeping Young People Safe, or jump to another chapter that sparks your interest.